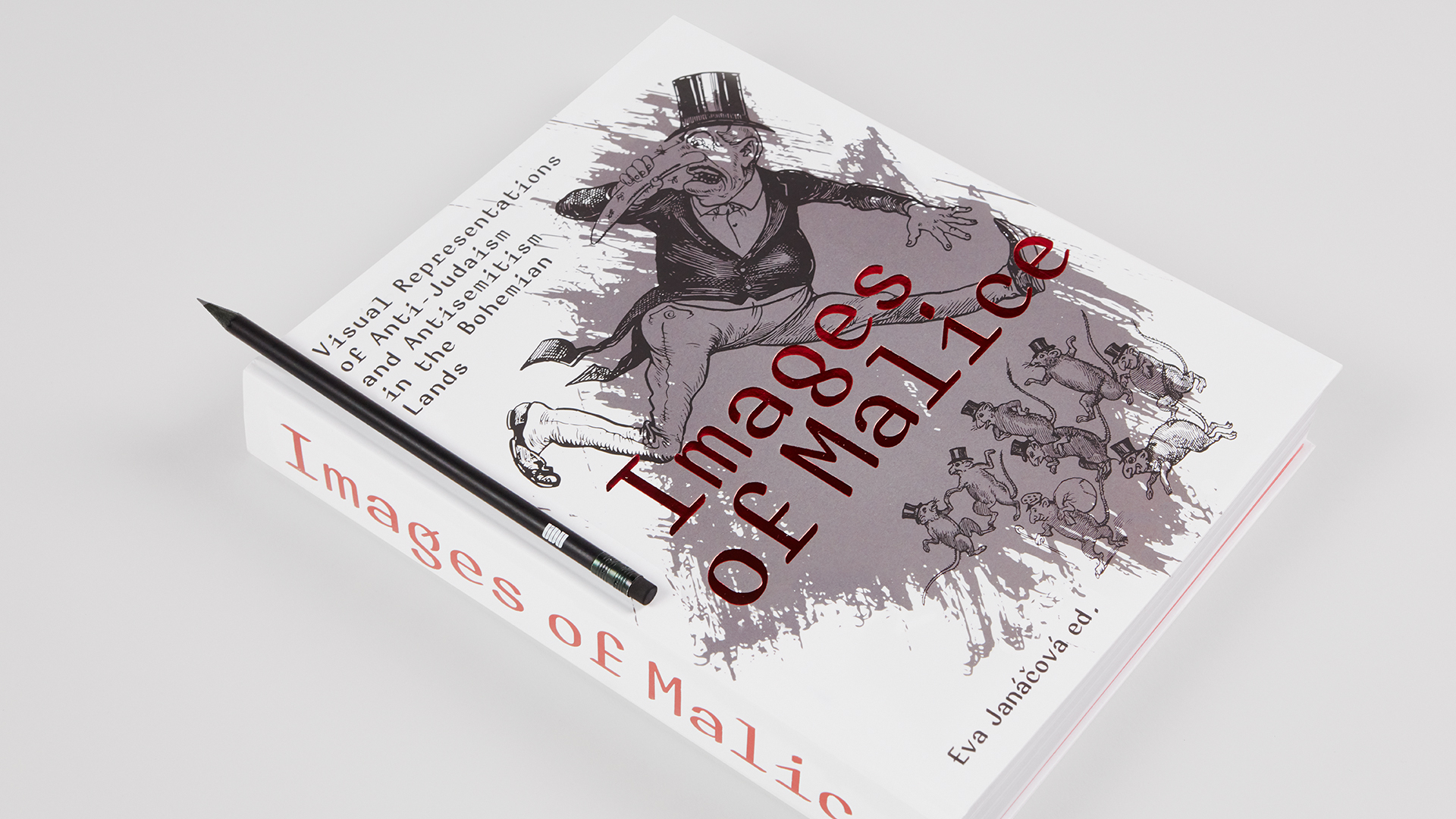

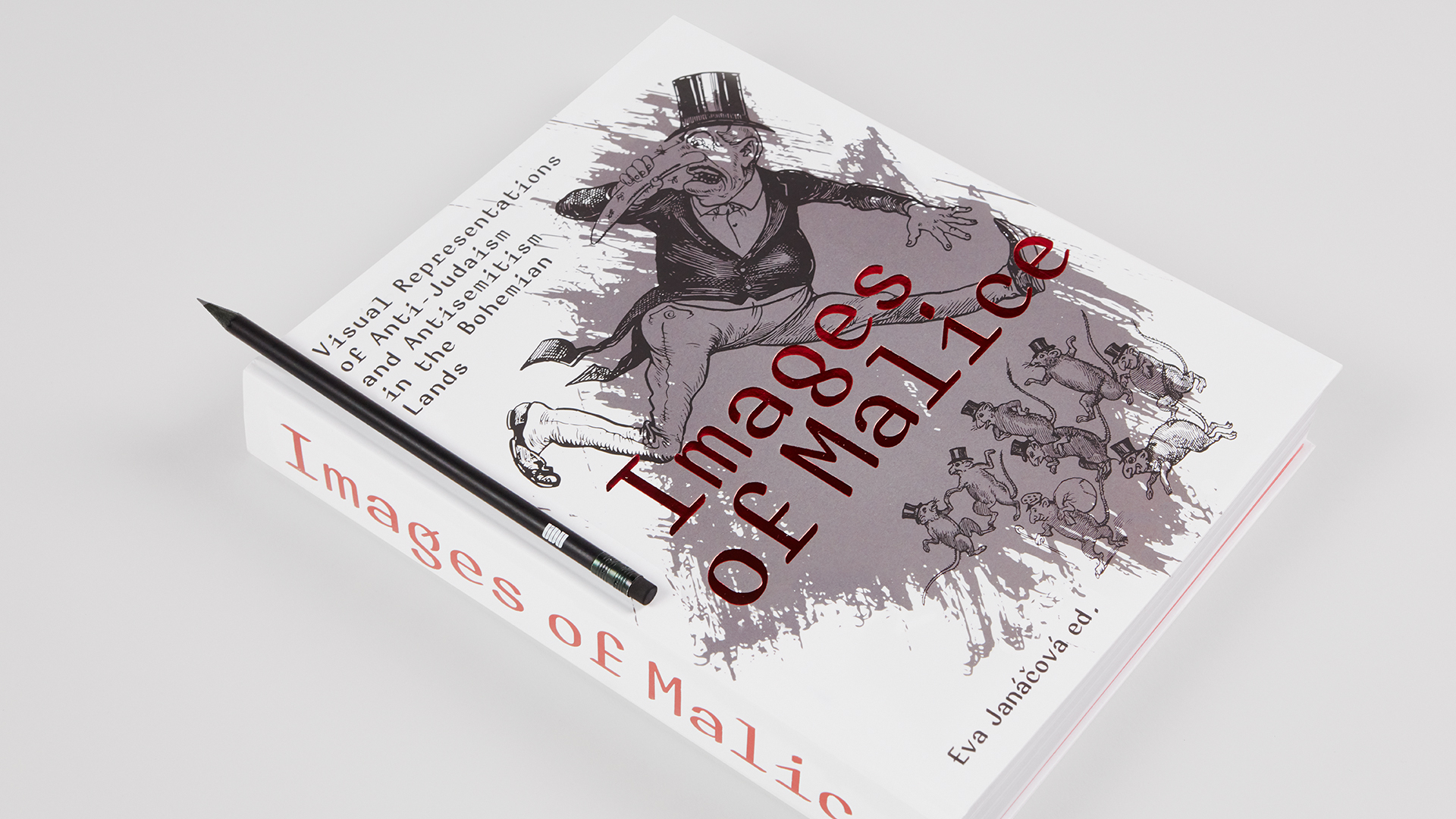

Eva Janáčová (ed.)

The subject of visual anti-Judaism (hatred of Jews based on their religious difference) and of visual antisemitism (hateful content based primarily on delineation of nationality) is an integral part of local histories in the Bohemian lands, whether that be the history of religion or the history of national and racial intolerance. This intolerance may have originated from church doctrines, from feudal fiats and, later in history, from conditions related to nationality and the general need to find somebody to blame for practically any kind of problem in society. The publication presents the well-known high points of antisemitic resentment on the one hand, while on the other hand it reconsiders our view of historical periods not usually connected with the idea of anti-Jewish sentiment. The danger of anti-Jewish visuals is still an urgent problem today. This mapping of the visual signs of anti-Judaism and antisemitism is also an account of their broader meaning, as the processes of stereotyping, delegitimization, dehumanization and exclusion from society represent a more general problem. Whether these processes target religious, national or sexual minorities, they are based on a supposed conflict that is both constructed and imaginary.

Texts: Alice Aronová, Daniel Baránek, Jan Dienstbier, Michal Frankl, Jakub Hauser, Eva Janáčová, Milan Pech, Daniel Soukup, Blanka Soukupová, Zbyněk Tarant

First Edition in English, colour illustrations, 406 pp., Prague 2022

ISBN 978-80-88283-67-6 (Artefactum)

ISBN 978-80-246-5105-7 (Karolinum)

The book won the award for the best graphic work of the publishing house Academia in the year 2021.

International distribution is provided by Chicago Press. You can order the book here

If you want to send the book to the Czech Republic, click below.

Introduction

This book features motifs in its cover design that have been taken from drawings printed in the Humoristické listy [Humorist Journal] periodical in the late 19th century, and as far as anti-Jewish visual culture goes, they are part of its typical arsenal. Such visuals have become both the intellectual and the material manifestations of the position held by the majority society toward the Jewish minority in the Czech lands, which has for the most part been complicated, historically speaking, and long. Through the history of this coexistence, resentment, ridicule and at some points open hostility and violence against Jews have manifested in different forms and in different intensities. Sometimes these forms have been clearly discernable, while at other times they have been more concealed, like these cover drawings: While an exaggerated nose need not necessarily be ascribed to Jews only, it exploits the principle of a symbol that, since the late 19th century, has become such a well-worn element that even today we can easily identify it, and while displaying Jews as rodents, vermin, or other parasites could have been considered a less conspicuous element in the humorous illustrations of the 19th century, the reason for doing so is much more radical, as such an illustration uncompromisingly excludes Jews from the nation as an absolutely divergent, undesirable element. This publication endeavors to describe and analyze both the blatant manifestations of anti-Judaism and antisemitism as well as their less visible or more latent manifestations in the Czech lands or in areas with a demonstrable tie to the Czech lands from the Middle Ages to the present.

The subjects of anti-Judaism, the hatred of Jews based on their different religion, and of antisemitism, hateful content based chiefly on definitions of nationality, are quite broadly represented in visual culture. This represents a dark yet integral component of local histories of national, racial and religious intolerance. This hatred originated in church doctrines, in feudal fiats, and later in the prerequisites for nationhood and the general need to find ‘the culprit’ responsible for practically any kind of problem in society. A constructed image of a collective enemy, as a figment of the imagination, has accompanied this coexistence throughout its entire history and, in an essential way, has contributed to creating the majority society’s negative image of the Jewish community.

This publication is one of the outcomes of a four-year grant project, The Image of the Enemy. Visual Manifestations of Antisemitism in the Czech Lands from the Middle Ages to the Present, no. DG18P02OVV039, financed by the Czech Culture Ministry’s NAKI II program (2018–2021). It builds on the findings of Special Maps Set. Visual Manifestations of Anti-Judaism and Antisemitism in the Czech Lands, available in book form and online, and especially on the collective monograph Visual Antisemitism in Central Europe. Imagery of Hatred. Unlike the latter monograph, this book concentrates specifically on the geographical area of the Czech lands, and also endeavors simultaneously to cover the subject both in more detail and more holistically, thereby presenting readers with the continuity of the anti-Jewish sentiments that never disappeared during any of the historical moments in this part of the world. This book also fundamentally expanded the circle of materials subjected to analysis, which then created the basis for an exhibition of the same name held under the auspices of Israeli Ambassador Anna Azari and the Governor of the Liberec Region, Martin Půta, from 1 October 2021 to 2 January 2022 at the Liberec Regional Gallery.

The broad chronological coverage of this particular monograph maps the anti-Jewish visual culture connected with medieval and Renaissance prejudices based in religion, the rise of antisemitism as a race-related phenomenon in the modern era of the 19th century, its catastrophic consequences in the 20th century, and the current growth in hateful manifestations of this kind in the environment of the Internet and social media. The publication shows anti-Judaism and antisemitism to be current subjects, revealing the fragile line between apparently innocent prejudices against the Jewish minority and those that segregate them from the rest of society, the line between what are allegedly humorous stereotypes and dangerous grudges and violence.

Visual culture contributes to forming our ideas about the world in a fundamental way, but in historical research it has been frequently underestimated (unlike textual, written culture), pushed into the background, and comprehended just as something extra, as the illustration of a message conveyed primarily in written form. Our endeavor, therefore, has been to investigate the history of antisemitism in relation to visual culture and art history, expanding thereby the research that has been done so far to include this dimension that has been so frequently forgotten. This publication includes nine studies, most of which come from the area of art historical research or of visual studies as more broadly conceived. These studies present a wide range of both artistic output and of materials that are not categorized as fine art. The selections in this publication thus extend from ‘high’ art to mass-produced visuals and also to areas unrelated to art per se.

The book is divided into two basic parts, the first of which discusses visual manifestations of anti-Judaism, the second of which discusses antisemitism in the Czech lands, and then a brief examination of the world of film is added at the end. The first chapter, by Jan Dienstbier and Daniel Soukup, maps the beginnings of anti-Jewish visuality in the 12th–15th centuries. The image of Jews in medieval fine art was subjected to the theological interpretation of their role in Christian history of the salvation of humanity. Jews were chiefly perceived as Christ’s murderers and enemies of the Christian faith, and frequently illustrations of them reflected negative phenomena from the Christian majority society. The images of Jews did not reflect reality, in today’s sense of the word, but reflected an ideal world where positive and negative values were clearly fixed in place. The next contribution from the same authors covers such iconography on the threshold of the early Renaissance, demonstrating how the form of medieval culture transformed as of the second half of the 15th century in a fundamental way through the dissemination of graphic printing and letterpress. The woodcuts, copper plate engraving, and other related techniques facilitated the rapid spread of print templates across Europe. Logically, they were also important to the forms of anti-Jewish iconography produced in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia. The adaptation and dissemination of anti-Jewish subjects and images thus was able to happen more effectively and faster, which also caused the erasure of local specificities to a significant degree. The next chapter by Daniel Baránek concentrates chiefly on church art during the early Renaissance, which was meant to contribute to constructing a coherent, mono-religious, pious society, to close it off to alien influences, or even to legitimize the anti-Jewish policies of repression underway at the time. Images of Jews dressed in stigmatizing, present-day attire were frequently inserted into illustrations of New Testament scenes, thereby presenting Jews as the eternal archenemy, as descendants of ‘Christ’s murderers’ who even in the present time were allegedly actively assaulting Christian society.

The second section of the book, dedicated to the subject of antisemitism in modernity, opens with a study by Michal Frankl who reflects on opportunities for exploring the relationship between visual studies and research into the history of antisemitism as a modern, race-based phenomenon. He shows that the forming of the anti-Jewish visual vocabulary and its consolidation during the 19th century cannot be exactly circumscribed by the recognized milestones of the era as defined, for example, by the rise of political parties with antisemitic programs. Using the examples of antisemitic illustrations from Czech humor magazines, he endeavors to provide suggestions for investigating the interplay between media, between anti-Jewish images and anti-Jewish texts. Jakub Hauser and Eva Janáčová have compiled a chapter on the period of the ‘Long 19th Century’, which is associated both with the emancipation of the Jews and with the birth of antisemitism in modernity as it relates to race. The chapter hinges on mapping illustrated periodicals published during the last third of the 19th century, when it was exactly such humorous imagery on the pages of periodicals that became the leading platform for disseminating both anti-Jewish and nationalist propaganda, including incipient racism. This includes the reflections of Leopold Hilsner’s show trial in visual output of the time. The next piece, by Milan Pech, covers the period of 1914 to 1945, clearly demonstrating how deeply engrained the foundations of antisemitism were in local society, which is documented, for example, through Czech folk culture. The author also observes the aspects of these anti-Jewish stereotypes and delegitimization strategies that are psychological in character. From these it is evident that visual manifestations of hate for Jews were not at all exceptional during the First Czechoslovak Republic and that they only intensified during the Nazi occupation. Particular attention is paid to the illustrator and painter Karel Rélink.

The complex days after the Second World War are covered by Blanka Soukupová. The antisemitic content of drawings resurfaces at the turn of the 1950s, when political show trials were transpiring in Czechoslovakia, frequently with openly antisemitic tendencies. At that time, political cartoonists began using symbols of the State of Israel to represent the collective Jew. Jewishness in and of itself was associated at the time with cosmopolitanism, with imperialism, and with what was called bourgeois nationalism. That trend continued even after the beginning of de-Stalinization in 1956. Anti-Israel caricatures diminished during the Prague Spring, when what appeared instead were flattering pictures of intellectuals who were Jewish and left-wing, but anti-Zionist drawings then returned during the decades of ‘normalization’. The penultimate chapter, by Zbyněk Tarant, maps the new visual forms of anti-Jewish prejudice from November 1989 to the close of 2020. He recalls several incidents that became known to the public and were characterized frequently by the interweaving of both a negative and a positive stereotype in folk art and popular culture, at times driven by ideas that were naive or romanticized. Attention is also paid to the skinhead scene, to esoterica, and to conspiracy theories, which demonstrate the distinct fluidity and flux of antisemitism today, which in certain cases manages to develop faster than the legal and theoretical definitions we use for this phenomenon. Alice Aronová’s investigation into the world of cinematography is the final contribution. Her study traces the domestic development of antisemitic content in cinematography as well as in the film industry from the 1930s to the 1980s. In addition to the Protectorate period, she considers the stifling atmosphere of the 1950s, which introduced more censorship and an attempt to suppress anything Jewish in contemporary film. After a brief relaxation during the 1960s, a period of intensified censorship returned once more during “normalization”, a time of managed propaganda and of limitations on the production of works by Jewish authors, as well as a related absence or minimization of Jewish subject matter.

The way in which we think about, write about, and explore antisemitism corresponds, to a great degree, to the current state of society. Under no circumstances can we close our eyes to the anti-Jewish content of either the past or the present, or pretend that it does not exist. On the contrary, it is only by studying such content, by analytically and synthetically reflecting upon it, that we can comprehend the mechanisms of its existence and continuity. It is possible to achieve the suppression of these hateful, ideological manifestations, which lead to both verbal and physical violence, by means of targeted education aimed at the more general questions of the formation of stereotypes and the danger of any intolerance to coexistence in a diverse society, as well as by adhering consistently to the domestic framework of laws proscribing antisemitism as one form of the defamation of a nation or religion.

In conclusion, some editorial notes. We have spelled antisemitism without the hyphen on the recommendation of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) and other international organizations devoting themselves to antisemitism, because antisemitism is not hatred of ‘Semitism’ or ‘Semites’; antisemitism is Jew-hatred. However, where quotations from sources and expert studies are concerned, we have consistently preserved the original spelling of all words and have not edited the expressions in any way. In cases where we have not given the names of the authors of the artworks in the text, in the notes or labels, it is because they are not known.